Jacob Emden

This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: Needs cleanup, esp. published works section. (February 2024) |

Jacob Emden | |

|---|---|

Rabbi Jacob Emden | |

| Personal life | |

| Born | June 4, 1697 |

| Died | April 19, 1776 (aged 78) Altona, Holstein, Holy Roman Empire |

| Children | Meshullam Solomon |

| Parent |

|

| Signature | |

| Religious life | |

| Religion | Judaism |

| Buried | Jewish Cemetery, Altona, Hamburg |

Jacob Emden, also known as the Yaʿavetz (June 4, 1697 – April 19, 1776), was a leading German rabbi and talmudist who championed traditional Judaism in the face of the growing influence of the Sabbatean movement. He was widely acclaimed for his extensive knowledge.[1][2]

Emden was the son of the hakham Tzvi Ashkenazi and a descendant of Elijah Ba'al Shem of Chełm. He spent most of his life in Altona (now part of Hamburg, Germany).[3] His son, Meshullam Solomon, served as rabbi of the Hambro Synagogue in London and claimed authority as Chief Rabbi of the United Kingdom from 1765 to 1780.[4]

The acronym Yaʿavetz (יעב״ץ, also rendered Yaavetz) is formed from his Hebrew name, Yaʿkov ben Tzvi (יעקב בן צבי).[5]

Seven of his 31 works were published posthumously.

Biography

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Jewish philosophy |

|---|

|

Early life and education

[edit]Jacob Emden (born Ashkenazi)[6] was the fifth of his father's 15 children.[7] Until the age of seventeen, he studied Talmud under his father, Tzvi Ashkenazi, a foremost rabbinic authority, first in Altona and later in Amsterdam (1710–1714). In 1715, he married Rachel, daughter of Mordecai ben Naphtali Cohen, rabbi of Ungarisch-Brod in Moravia (now Uherský Brod in the Czech Republic) and continued his studies in his father-in-law's yeshiva. [8]

Emden mastered all branches of Talmudic literature and later expanded his studies to philosophy, kabbalah, and grammar—even attempting to learn Latin and Dutch despite his view that secular studies should be limited to periods when Torah study was not feasible.[8]

Career

[edit]Emden initially spent three years in Ungarisch-Brod as a private Talmudic lecturer before taking up work as a dealer in jewelry and other goods—a trade that required extensive travel.[8] Although he generally declined formal rabbinic positions, in 1728 he accepted the rabbinate of Emden, from which he later derived his name.[8] He eventually returned to Altona, where he secured permission from the Jewish community to establish a private synagogue. Early on, he enjoyed cordial relations with Moses Hagiz, head of the Portuguese Jewish community in Altona, though these later deteriorated due to calumnies. Similarly, his initially positive relations with the chief rabbi of the German community, Ezekiel Katzenellenbogen, later soured.[9]

A few years later, Emden obtained permission from the King of Denmark to establish a printing press in Altona. He soon encountered controversy over his publication of a siddur he wrote in 1747 with commentary[10] according to the minhag Polin, ʿAmmude Shamayim (עמדי שמים),[11] harshly criticizing influential local moneychangers. Despite receiving the approbation of the Landesrabbiner, his opponents continued to denounce him.[8]

Ya'avetz Pen Name

[edit]In the preface to his work Responsa of Yaavetz,[12] Emden recounts how, as a child, he questioned why his father signed only as "Tzvi" (צבי) rather than also including his father's name as was the norm. His father explained that this was a homonym, Tzv״i (צב״י): an acronym for his full name, Tzvi ben Yaʿakov (צבי בן יעקב). He advised that Emden should take the pen name Ya'avetz (יעב״ץ) under the same principles. The Hebrew name Yaʿavetz appears both as a place name in 1 Chronicles 2:55 and a personal name in 4::9-10..[13]

Sabbatean controversy

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Kabbalah |

|---|

|

Emden accused Jonathan Eybeschutz of being a secret Sabbatean, a heretical belief. The controversy lasted several years, continuing even after Eybeschutz' death. Emden's assertion of Eybeschutz' heresy was chiefly based on the interpretation of kabbalistic amulets prepared by Eybeschutz, in which Emden saw Sabbatean allusions. Hostilities began before Eybeschutz left Prague. In 1751, when Eybeschutz was named chief rabbi of the three communities of Altona, Hamburg, and Wandsbek, the controversy reached the stage of intense and bitter antagonism. Emden maintained that threats initially prevented him from publishing anything against Eybeschutz. He solemnly declared in his synagogue the writer of the amulets to be a Sabbatean heretic and deserving of ḥerem, shunning by the Jewish community.[8] Emden's "Megillat Sefer" accused Eybeschutz of having an incestuous relationship with his daughter and of fathering a child with her. However, allegedly the "Megillat Sefer" was tampered with and had deliberately ridiculous accusations and narratives added to mock Emden.[14]

Clashes between opposing supporters occurred in the streets, drawing the secular authorities' attention according to the "Kuryer Polski" of June 16, 1751. The majority of the community, including Aryeh Leib Epstein of Königsberg, favored Eybeschutz. The council, therefore, condemned Emden as a slanderer. Under pain of ḥerem, people were ordered not to attend Emden's synagogue, and he was forbidden to issue anything from his press. Since Emden continued his philippics against Eybeschutz, he was ordered by the council of the three communities to leave Altona. He refused to, relying on the strength of the King's charter, and he maintained he had been relentlessly persecuted. In May 1751, he finally took refuge in Amsterdam when it seemed his life was in danger. He had many friends there and joined the household of his brother-in-law, Aryeh Leib ben Saul, rabbi of the Ashkenazi Jews there.

The controversy was heard by both the Senate of Hamburg and the Royal Court of Denmark. The Hamburg Senate quickly found in favour of Eybeschutz.[15] King Frederick V of Denmark asked Eybeschutz to answer questions about the amulets. Conflicting testimony was put forward, and the matter remained officially unresolved, according to Grunwald, in the Hamburgs deutsche Juden 107. However, the court sentenced the council of the three communities to pay a fine of one hundred thaler for civil unrest and ordered Emden to return to Altona.[16]

Emden then returned to Altona and took possession of his synagogue and printing establishment, though he was forbidden to continue his agitation against Eybeschutz. The latter's partisans, however, did not desist from their warfare against Emden. They accused him before the authorities of continuing to publish denunciations against his opponent. One Friday evening (July 8, 1755), his house was broken into and his papers seized and turned over to the "Ober-Präsident" (royally imposed mayor), Henning von Qualen (1703–1785). Six months later, Qualen appointed a commission of three scholars, who, after a close examination, found nothing which could incriminate Emden. Eybeschutz was reelected as Chief Rabbi. In December that year, the Hamburg Senate rejected the King's decision and the election result. The Senate of Hamburg started an intricate process to determine the powers of Eybeschutz as Chief Rabbi. The truth or falsity of his denunciations against Eybeschutz cannot be proved; Gershom Scholem wrote much on this subject, and his student Perlmutter devoted a book to proving it. According to historian David Sorkin, Eybeschutz was probably a Sabbatean,[17] and Eybeschutz's son openly declared himself to be a Sabbatean after his father's death. Further background suggests that Eybeschutz may have been a Sabbatean. In July 1725, the Ashkenazi beth din of Amsterdam issued a ḥerem on the entire Sabbatean sect (כת המאמין kaṯ hammaʾamin) based partially on the discovery of Sabbatean writings. Ezekiel Katzenellenbogen, Chief Rabbi of the Three Communities[18] was unwilling to attack Eybeschutz publicly, but stated that one of the Sabbatean texts found by the Amsterdam beth din, Va’avo hayyom el-haʿayin (Hebrew: וָאָבֹא הַיּוֹם אֶל־הָעָיִן, romanized: Wāʾāb̲o hayyom el-hāʿāyin, lit. 'I came today to the spring'[a]), was authored by Eybeschutz and declared that all copies of the work that were in circulation should be immediately burned.[19] The recent discovery in Metz of notarial copies of the disputed amulets written by Eybeschutz supports Emden's view that these are Sabbatean writings.[20]

Other notable events

[edit]

In 1756, the members of the synod of Starokostiantyniv (Yiddish: אלט-קאָנסטאַנטין, romanized: Alt Konstantin) in the Volhynian Voivodeship (now western Ukraine) requested Emden aid them in repressing the Sabbateans and Frankists. As the Sabbateans referred much to the Zohar, Emden thought it wise to examine that book, and after a careful study he concluded that a significant part of the Zohar was the production of an impostor.[21]

Emden's works show critical powers rarely found among his contemporaries. He was strictly orthodox, never deviating the least from tradition, even when the difference in time and circumstance might have warranted a deviation from custom. Emden's opinions were often viewed as extremely unconventional from the perspective of strictly traditional mainstream Judaism, though not so unusual in more free-thinking Enlightenment circles. Emden had friendly relations with Moses Mendelssohn, founder of Haskalah, and with several Christian scholars.[22]

In 1772, Frederick II, Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin issued a decree forbidding burial on the day of death. The Jews in his territories approached Emden with the request that he demonstrate a Talmudic ruling that a more prolonged exposure of a corpse would be against Jewish burial customs. Emden referred them to Mendelssohn, who greatly influenced Christian authorities and wrote in excellent German. Mendelssohn wrote the requested letter to the Duke. However, he privately complained to Emden that the Duke was correct based on his understanding of the Talmud. Emden wrote to him in strong terms, saying that it was ludicrous to assert that the custom of the entire Jewish people was blatantly incorrect and told Mendelssohn that this kind of claim would only strengthen rumors of irreligiousness Mendelssohn had aroused by his associations.[23]

Views

[edit]Emden was a traditionalist who responded to the ideals of tolerance being circulated during the 18th-century Enlightenment. He stretched the traditional inclusivist position into universal directions.[24] Like Maimonides, he believed that monotheistic faiths have an important roles to play in God's plan for mankind, writing that "we should consider Christians and Muslims as instruments for the fulfilment of the prophecy that the knowledge of God will one day spread throughout the earth."[25] Emden praised the ethical teachings of Christianity, considering them beneficial in removing the prevalence of idolatry and bestowing gentiles with a "moral doctrine".[2][26] Emden also suggested that ascetic Christian practices provided additional rectification of the soul in the same way that Judaic commandments do.[2]

In many ways, Emden was a nuanced figure who navigated the tension between rabbinic and external historical sources. Emden often tempered the exclusionist approach of scholars like Aviad Sar-Shalom Basilea, who outright rejected non-rabbinic sources, by cautiously engaging with external historical claims. For example, in addressing contradictions between Talmudic and historical accounts, Emden sometimes reinterpreted rabbinic texts to align with external evidence, as seen in his treatment of the Talmudic story about Nero’s conversion. He also critiqued Azariah dei Rossi for uncritically accepting non-Jewish sources, but stopped short of branding him a heretic, instead viewing him as misguided. Emden’s approach reflects a balance between preserving the authority of rabbinic literature and cautiously integrating external historical insights, making him a moderate voice in the debate over the historicity of rabbinic claims.[27]

He theoretically advocated the pilegesh (biblical concubinage), since the Sages stated "the greater the man, the greater his evil inclination", and cited many sources in support.[28][29] He also suggested it might be permissible under certain circumstances for a Jewish man to cohabit with a single Jewish woman, provided that she is in an exclusive relationship with him that is public knowledge and where she would not be embarrassed to attend the mikveh. He also wished to revoke the ban on polygamy instituted by Gershom ben Judah, believing it erroneously followed Christian morals. However, he admitted he lacked the power to do so.[3]

Emden wrote that he owned books containing secular wisdom written in Hebrew but would read them in the bathroom.[30] He was opposed to philosophy and maintained that the views contained in The Guide for the Perplexed could not have been authored by Maimonides, but rather by an unknown heretic.[3]

Works

[edit]

Jacob Emden’s corpus spans halakhic, liturgical, kabbalistic, and polemical writings—with some works jointly attributed to him and his father. His published writings include:

- Edut BeYaakov (Altona, Hamburg, 1756) – Addresses the alleged heresy of Eybeschütz, including the letter Iggeret Shum to the rabbis of the Four Lands.

- Shimmush (Amsterdam, 1758–62) – Comprises three works: Shoṭ la‑Sus, Meteg laHamor (against the influence of the Sabbateans), and Sheveṭ leGev Kesilim, a refutation of heretical demonstrations.

- Shevirat Luchot haAven (Altona, 1759) – A refutation of Eybeschütz’s Luchot Edut.

- Sechok haKesil, Yekev Ze'ev, and Gat Derukhah (Altona, 1762) – Three polemical works published in the *Hit'abbekut* of one of his pupils.

- Mitpachat Sefarim (Altona, 1761–68) – In two parts: the first demonstrates that part of the Zohar is a later compilation; the second criticizes works such as Emunat Hakhamim and Mishnat Hakhamim as well as various polemical letters.

- Herev Pifiyyot, Iggeret Purim, Teshuvot haMinim, and Zikkaron beSefer – On money changers and bankers (unpublished).

- Lechem Shamayim (Altona, 1728; Wandsbeck, 1733) – A commentary on the Mishnah with a treatise on Maimonides’ Mishneh Torah (Beit haBechirah).

- Iggeret Bikkoret (Altona, 1733) – Responsa.

- She'elat Ya'abetz (Altona, 1739–59) – A collection of 372 responsa.

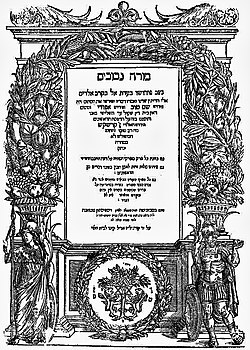

- Siddur Tefillah (Altona, 1745–48) – An edition of the prayer book featuring commentary, grammatical notes, ritual laws, and treatises (including Beit‑El, Sha'ar haShamayim, and Migdal Oz); also contains the treatise Even Bochan and a critique of Menahem Lonzano’s Avodat Mikdash (titled Seder Avodah).

- Etz Avot (Amsterdam, 1751) – A commentary on Pirkei Avot, with grammatical notes compiled in Lechem Nekudim.

- Sha'agat Aryeh (Amsterdam, 1755) – A eulogy for his brother‑in‑law, Aryeh Leib ben Saul (rabbi of Amsterdam); also included in his Kishurim leYaakov.

- Seder Olam Rabbah and Seder Olam Zutta (Hamburg, 1757) – The texts of Seder Olam and Megillat Ta'anit, edited with critical notes.

- Mor uKetziah (Altona, 177?) – Novellæ on Orach Hayyim (with additional novellæ on Yoreh Deah, Even haEzer, and Hoshen Mishpat remaining unpublished).

- Tzitzim uFerachim (Altona, 1768) – A collection of kabbalistic articles arranged alphabetically.

- Luach Eresh (Altona, 1769) – Grammatical notes on the prayers and a critique of Solomon Hena’s Sha'arei Tefillah.

- Shemesh Tzedakah (Altona, 1772).

- Pesach Gadol, Tefillat Yesharim, and Ḥoli Ketem (Altona, 1775).

- Sha'arei Azarah (Altona, 1776).

- Divrei Emet uMishpaṭ Shalom (Altona, 1776).

- Megillat Sefer (Warsaw, 1897) – Contains biographies of himself and his father.

- Kishurim leYaakov – A collection of sermons.

- Marginal novellæ on the Babylonian Talmud.

- Emet LeYaakov (Kiryas Joel, 2017) – Notes on the Zohar and assorted works, including Dei Rossi’s Meor Einayim.

His unpublished rabbinical writings include:

- Tza'akat Damim – A refutation of the blood libel in Poland.

- Hilkheta liMeshicha – A responsum to R. Israel Lipschütz.

- Mada'ah Rabbah.

- Gal‑Ed – A commentary on Rashi and the Targum of the Pentateuch.

- Em laBinah – A commentary on the entire Bible.

- Em laMikra velaMasoret – Also a commentary on the Bible.

Emden Siddur

[edit]20th-century printings of the Emden Siddur exist, notably the Lemberg edition (1904)[31] and the Augsburg edition (1948),[32] both bearing the cover title Siddur Beis Yaakov[33] (also anglicized as Siddur Bet Yaakov; Hebrew: סידור בית יעקב).[34] The covers identify the work as being by "Jacob from Emden" (יעקב מעמדין). The 472-page Lemberg 1904 printing includes Tikun Leil Shavuot on pages 275–305 and is considerably larger than Emden’s Shaarei Shamayim siddur.

Shaarei Shamayim

[edit]A physically smaller siddur, reprinted in Israel in 1994, was titled Siddur Rebbe Yaakov of Emden (Hebrew: סידור רבי יעקב מעמדין) on the upper half of the cover and Siddur HaYaavetz Shaarei ShaMaYim (סדור היעב"ץ שערי שמים) elsewhere. Its commentary is less detailed than that of the full Emden Siddur—for example, it omits Tikkun Leil Shavuot. This edition is presented as a two-volume set.

Notes

[edit]- ^ A reference of to Genesis 24:42, "Genesis 24:42". www.sefaria.org.

References

[edit]- ^ Communicated with Moses Mendelssohn, founder of the breakaway Haskalah movement: "A 19th‑century copy of a 1773 letter from Moses Mendelssohn to Rabbi Jacob Emden".

- ^ a b c Falk, Harvey. "Rabbi Jacob Emden's Views on Christianity" Journal of Ecumenical Studies, Volume 19, no. 1 (Winter 1982), pp. 105–11.

- ^ a b c Louis Jacobs (1995). The Jewish Religion: A Companion. Oxford University Press. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-19-826463-7.

- ^ Jacob Emden (May 4, 2011). Megilat Sefer: The Autobiography of Rabbi Jacob Emden (1697–1776). PublishYourSefer.com. p. 353. ISBN 978-1-61259-001-1.

- ^ "Yaakov Israel (Yaakov Emden, Ya'avetz) Emden (Ashkenazi) Sidur".

- ^ "Rabbi Jacob Emden".

- ^ "Rabbi Tzvi Hirsch "Chacham Tzvi" Ashkenazi, Chacham Zvi".

- ^ a b c d e f Solomon Schechter, M. Seligsohn. Emden, Jacob Israel ben Zebi, Jewish Encyclopedia (1906).

- ^ Jacob J. Shachter (1988). Rabbi Jacob Emden: Life and Major Works. Cambridge, Massachusetts. p. 107.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Schacter, Jacob J (1992). "The Siddur of Rabbi Jacob Emden: From Commentary to Code". In Link-Salinger, Ruth (ed.). Torah and Wisdom, Torah ve-Hokhmah: Studies in Jewish Philosophy, Kabbalah, and Halacha – Essays in Honor of Arthur Hyman. New York: Shengold. p. 175.

- ^ "SIDDUR (DAILY PRAYER BOOK) ACCORDING TO THE POLISH RITE WITH AN EXTENSIVE COMMENTARY AND ESSAYS BY RABBI JACOB EMDEN, ALTONA: [RABBI JACOB EMDEN], 1744-1748". www.sothebys.com. Sotheby's.

- ^ "Sheilat Yaavetz". www.sefaria.org. Sefaria.org.

- ^ Sol Steinmetz (2005). Dictionary of Jewish Usage: A Guide to the Use of Jewish Terms. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 79. ISBN 9780742543874.

- ^ Gestetner, Avraham Shmuel Yehuda. מגילת פלסתר [Megilas Plaster] (in Hebrew). Monsey, NY.

- ^ Grunwald Hamburgs deutsche Juden 103-105

- ^ Emden Edut be Ya'akov 10r 63r

- ^ David Sorkin, "The Transformation of German Jewry, 1780–1840", Wayne State University Press, 1999, p. 52.

- ^ Gahalei Esh, Vol. I, fol. 54

- ^ Prager, Gahalei Esh, Vol. I, fol. 54v.

- ^ Leimann, Sid Z.; Schwarzfuchs, Simon (May 1, 2006). "New Evidence on the Emden-Eibeschuetz Controversy". Revue des Études Juives. 165 (1): 229–249. doi:10.2143/REJ.165.1.2013881.

- ^ Taken from the Public Domain Jewish Encyclopedia article

- ^ The Jewish enlightenment, by Shmuel Feiner, ch. 1, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003

- ^ Sheilat Yaavetz, by Jacob Emden, Volume three, siman 44–47, new edition of Keren Zichron Moshe Yoseph, 2016

- ^ Rabbi Dr. Alan Brill. Judaism and Other Religions: An Orthodox perspective Archived January 20, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, commissioned by the World Jewish Congress for the World Symposium of Catholic Cardinals and Jewish Leaders (January 2004).

- ^ Gentile, Jewish Encyclopedia (1906).

- ^ Sandra B. Lubarsky (November 1990). Tolerance and transformation: Jewish approaches to religious pluralism. Hebrew Union College Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-87820-504-2. Retrieved July 19, 2011.

- ^ Klein, Reuven Chaim (2023). "Are historical sections of the Talmud actually historical? Critical tools for understanding historical claims in rabbinic literature". Journal of Philological Pedagogy. 12. Chandler School of Education: 42–75. doi:10.17613/rjp5a-md343.

- ^ עמדין, יעקב בן צבי (1884). שאילת יעבץ. Lemberg. p. חלק ב סימן טו. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Winkler, Gershon. "The responsum of Rabbi Yaakov Emden from Sheylot Ye'avitz, vol. 2, no. 15" (PDF). Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Keeping the Jewish Camp Holy (series, part 34)". Torah Tavlin. January 3, 2015. p. 4.

- ^ "Jacob Emden Yaabetz Siddur".

Reprint of the popular Emden Siddur (Lemberg 1904

- ^ "Siddur Bet Yakov". Archived from the original on May 23, 2019. Retrieved May 23, 2019.

Printed by and for the use of Holocaust survivors in liberation camps. ... dedicated to

- ^ "Shemoneh Esrei 34: Davening For The Majority Part I". OU.org.

- ^ Reuven P. Bulka (1986). Jewish Marriage: A Halakhic Ethic. KTAV Publishing House. p. 218. ISBN 0881250775.

External links

[edit]- Emden, Jacob Israel Ben Zebi Ashkenazi, jewishencyclopedia.com

- Jacob Emden, jewishvirtuallibrary.org

- Rabbi Jacob Emden's View on Christianity and the Noachite Commandments, Reprinted from the Journal of Ecumenical Studies, 19:1, Winter 1982

- , from Shelyot Ye'avetz, v 2, 15

- Cohen, Mortimer J. (1948), "Was Eibeschuetz a Sabbatian?", The Jewish Quarterly Review, XXXIX (1): 51–62, doi:10.2307/1453087, JSTOR 1453087.

- Cohen, Mortimer Joseph, Jacob Emden, A Man of Controversy, Philadelphia, Dropsie College for Hebrew and Cognate Learning, 1937.

- Schacter, Jacob J., Rabbi Jacob Emden: Life and Major Works, Diss., Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts 1988.